In recent years the conversation surrounding the effects of blue light has been steadily growing. What began as investigations into the sleep cycle of photosynthetic marine plankton in the 1950s has rapidly progressed to today’s detailed research of the human response to different wavelengths and the impact it has on the many facets of our complicated physiology.1 The findings of this research seems to suggest that the wavelength of visible light that is most harmful to humans is at around 435 nm – blue-violet light on the visible spectrum.2 As the global population is increasingly exposed to blue-violet light due to everyday technology like smartphones, laptops and fluorescent lighting, the discussion of blue light hazards has found its way into the spotlight. Several tech companies like Apple, Microsoft and Samsung offer blue light filters for almost all of their digital products and blue light filter coatings for spectacle lenses are becoming more and more common. But how does blue light filtering stack up against the hype?

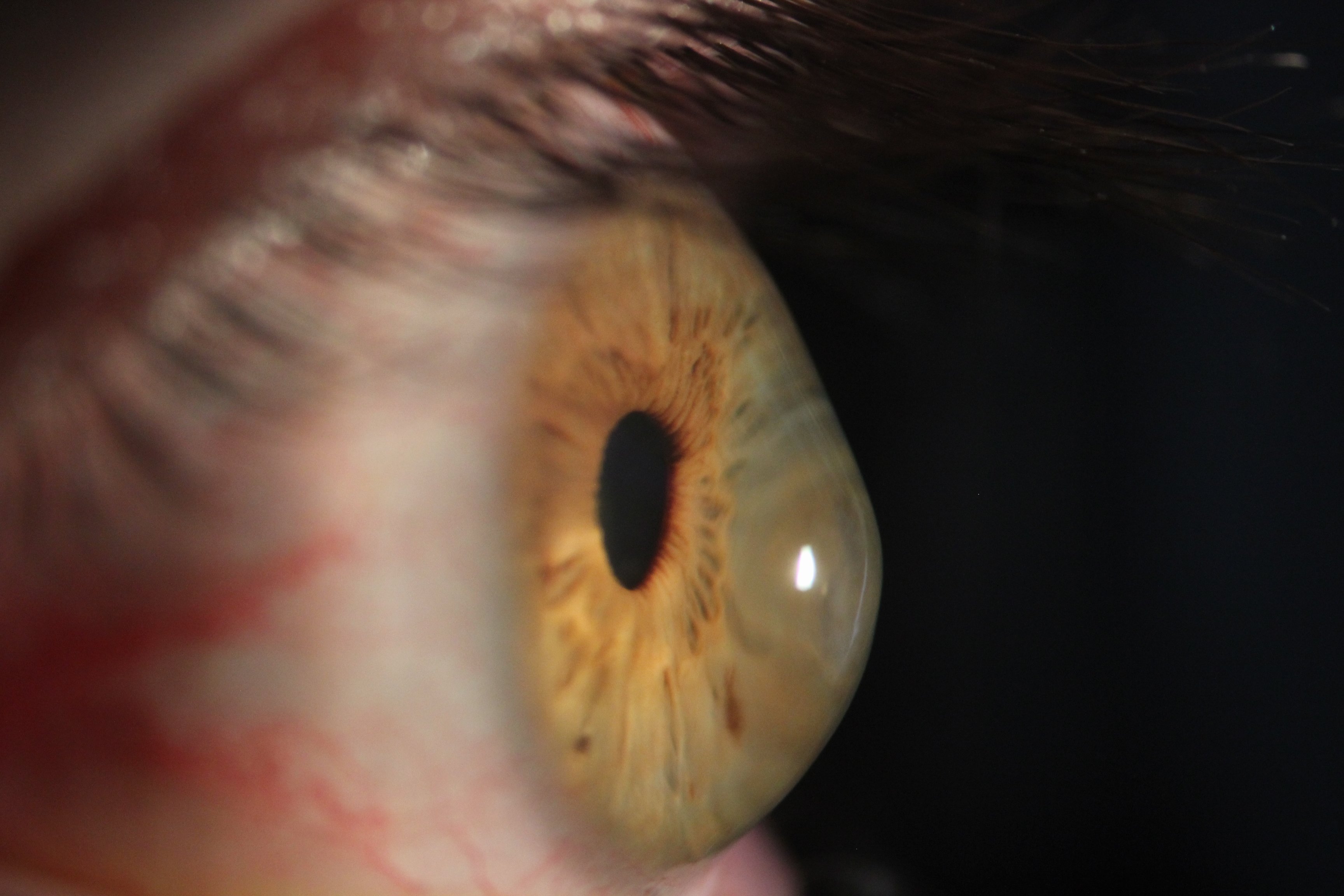

We’ve probably all heard of the dangers of UV light before and the multitude of ocular pathologies that can arise from exposure to the sun’s rays. Luckily, medium-wave ultraviolet B and short-wave ultraviolet C light is effectively filtered by the ozone layer and the lens of the eye.3 It’s the long-wave ultraviolet A light that can pass through both these media along with visible light to penetrate the macular pigment. Blue-violet light is similar to UVA light in that they are both comparably high energy wavelengths. This means that they can have powerful effects on the retina, and such effects are not always beneficial. Both have been linked to macular degeneration, although the relationship between MD and blue light exposure is more tenuous.4

You may be asking yourself why we don’t simply block all blue light like we do UV light if there’s accumulating evidence that blue light is detrimental. While UVA light can and should be effectively filtered with quality sunglasses, it is not always effective or practical to do the same for blue light. Unlike UVA, we need wavelengths of blue light to be able to see in scotopic and mesopic conditions – that is, low-light environments.3 Blue light is also necessary for the regulation of circadian rhythm. Retinal ganglion cells containing melanopsin pigment are stimulated by blue light to indirectly suppress melatonin release into the blood, which has the effect of reducing sleepiness.2 Its absence at night would normally, under the natural circumstances that humans have evolved under, trigger melatonin release and allow for the onset of sleep.

However, now that more and more of us are using digital devices before bed (as many as 70% of Australian adolescents)5 this sleep cycle is being interrupted. It follows then that blue light filtering is mostly necessary after dark when we would like to be able to sleep. As previously mentioned, there are settings on almost all digital devices to lessen blue light emission at certain times of the day. There are also options available in the form of spectacle lens add-ons that help to block blue light. The first of these is an anti-reflection coating, which gives the light reflected off the glasses a bluish hue, but most AR coatings generally only block about 10% of blue light that is emitted from digital devices.3 The lenses themselves can also be tinted an amber colour which can block much more blue light depending on the density, but these must be manufactured in accordance with legal requirements for night driving.3 Finally, different lens materials can block up to 100% of blue-violet wavelengths, but these often have a heavy yellowish-amber hue.

Recent research has shown that amber-tinted lenses have significant effects on those who use digital devices before bed, including insomniacs. Wearing these glasses for just three hours a night for two weeks increased melatonin levels in participants by 58% in one study, increasing sleep duration by 24 minutes.6 The insomniac study showed similar results, with participants experiencing about 30 extra minutes of sleep when tinted lenses were worn for 2 hours before bed.7 The common thread in each of these studies is that participants reported faster sleep onset and a deeper, more rejuvenating slumber.

At this point there is not much evidence to link blue light with serious ocular pathology like macular degeneration. Although we may not know all there is to know about the cause and effect relationship between blue light and disease, we know enough about the impact of blue light on circadian rhythm and its subsequent detriment to the body’s function to caution against excess exposure to blue light emissions, particularly late at night and in high levels.

References

- Holzman, David C. “What’s In A Color? The Unique Human Health Effects Of Blue Light”. Environmental Health Perspectives, vol 118, no. 1, 2010, pp. A22-A27. Environmental Health Perspectives, doi:10.1289/ehp.118-a22

- Marshall, John. “The Blue Light Paradox: Problem Or Panacea”. Mivision, 2017, http://www.mivision.com.au/the-blue-light-paradox-problem-or-panacea/

- Peaper, Nicola. “Controlling Light: Transmission, Reflection And Absorption By Spectacle Lenses”. Mivision, 2018, http://www.mivision.com.au/controlling-light-transmission-reflection-and-absorption-by-spectacle-lenses/

- Tosini, Gianluca et al. “Effects of blue light on the circadian system and eye physiology.” Molecular vision 22 (2016): 61-72.

- Gamble, Amanda L. et al. “Adolescent Sleep Patterns And Night-Time Technology Use: Results Of The Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Big Sleep Survey”. Plos ONE, vol 9, no. 11, 2014, p. e111700. Public Library Of Science (Plos), doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111700

- Ostrin, Lisa A. et al. “Attenuation Of Short Wavelengths Alters Sleep And The Iprgc Pupil Response”. Ophthalmic And Physiological Optics, vol 37, no. 4, 2017, pp. 440-450. Wiley, doi:10.1111/opo.12385

- “Selective Blue Block Helps Insomniacs”. Mivision, 2018, http://www.mivision.com.au/selective-blue-block-helps-insomniacs/

%20(1).png)